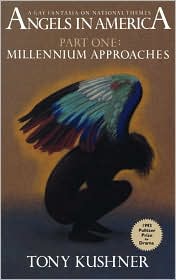

by Tony Kushner

directed by Jason Southerland and Nancy Curran Willis

presented by Boston Theatre Works

As I entered the Roberts Studio for Boston Theatre Work’s presentation of Millennium Approaches, I did a double take at the headshot-strewn bulletin board; surely that was not the whole cast! I panicked, running through the possibilities of BTW cutting one of the play’s beloved characters, or some other editing horror, but was calmed when I opened my program. All the players were accounted for, and everything seemed in order. For all of the hype (including, I realize, my own) of the epic scale and sweep of Kushner’s two-part Angels in America, the truth remains that it employs a modest cast of eight. Instead of looking to meet staggering expectations, and in the same vein of modesty as the cast size, Jason Southerland and Nancy Curran Willis (in a nifty co-directing scheme) keep their production of Tony Kushner’s Angels In America: Millennium Approaches utterly human and down-to-earth, grounded in their mostly solid ensemble. Instead of looking to transcend limitations (of both their company and budget), they accept and integrate them, making for a “fantasia” (as Kushner subtitles it) that is much more skilled in delivering mortal dealings than flights of fancy. Although this approach may not give its climax the wings to soar, the rest of Millennium does have the heart to captivate the audience in the entangled web of characters and relationships it details.

As I entered the Roberts Studio for Boston Theatre Work’s presentation of Millennium Approaches, I did a double take at the headshot-strewn bulletin board; surely that was not the whole cast! I panicked, running through the possibilities of BTW cutting one of the play’s beloved characters, or some other editing horror, but was calmed when I opened my program. All the players were accounted for, and everything seemed in order. For all of the hype (including, I realize, my own) of the epic scale and sweep of Kushner’s two-part Angels in America, the truth remains that it employs a modest cast of eight. Instead of looking to meet staggering expectations, and in the same vein of modesty as the cast size, Jason Southerland and Nancy Curran Willis (in a nifty co-directing scheme) keep their production of Tony Kushner’s Angels In America: Millennium Approaches utterly human and down-to-earth, grounded in their mostly solid ensemble. Instead of looking to transcend limitations (of both their company and budget), they accept and integrate them, making for a “fantasia” (as Kushner subtitles it) that is much more skilled in delivering mortal dealings than flights of fancy. Although this approach may not give its climax the wings to soar, the rest of Millennium does have the heart to captivate the audience in the entangled web of characters and relationships it details. And oh, what a wangled teb it is. Kushner orchestrates a series of what are mostly tightly scripted dialogues between his characters, bringing together disparate strands of his far-reaching story in surprising ways. In Millennium, we are introduced to two couples whose deterioration Kushner sets against the onset of AIDS in 1980s  The second duo is the distant Mormon marriage of Valium-dependant Harper (Bree Elrod) and closet-case, law clerk Joe (Sean Hopkins) whose boss, Kushner’s conjuration of the real-life Roy Cohn (Richard McElvain), has urged him to move to

The second duo is the distant Mormon marriage of Valium-dependant Harper (Bree Elrod) and closet-case, law clerk Joe (Sean Hopkins) whose boss, Kushner’s conjuration of the real-life Roy Cohn (Richard McElvain), has urged him to move to

When describing the characters, it can sometimes read like a rag-tag parade of tired stereotypes that we’ve all seen before and are bound to see again; The drag queen with a heart of gold, the closeted conservative, the uptight mother of sed closeted conservative, ect. But what is so immediate about Angels is the ways Kushner uses his unapologetically beautiful language with incomparable economy, exploding what we think we know in a matter of scenes. No persona get predominantly more stage time than another, yet by the end we feel as though we know each intimately. The specificity with which he conjures their desires and fears cuts right to the heart, which is perhaps a main reason for his success. Although Angels is undoubtedly a political play, the individuality of the characters is never put on the back burner in favor of preaching from pastor Kushner; instead, we are engaged in a delicate cross-section where gender, race, and sexuality brings together and shifts apart the characters. Most of the events and devices of the script would fall flat as amateur dramaturgical tricks if Kushner did not have the full-blooded people he populates Millenium with to bounce them off of, and in this sense his ideas fly.

Even with a somewhat manageable cast, both parts of Angels are no less a challenge to stage; the  cast all do double-, and triple- duty (including Nitter, left, who can now add Drag King to her resume) to populate the Roberts Studio with all of the aforementioned principle players, as well as some assorted nuts and phantoms. The story also location-hops without abandon, taking place in the parks and apartments of the city, as well as the dreamscapes and tundras of its character’s imaginations. Directors Southerland and Curran Willis, aided by the unfussy work of their capable design team, manage to keep Millennium moving at an admirable pace. Laura McPherson’s industrial wasteland of a set facilitates all of the necessary simultaneous staging (which often bothers me, but didn’t here), but seemed a little flimsy for the physicality of the production. More impressive were sound designer Nathan Leigh and lighting designer John Melinowki’s nuanced contributions. Melinowski clearly delineates all of the different locations of the play, and baths all of the more fantastic scenes in a hallucinogenic black light glow, and both Leigh’s musical compositions (dark sliding saxophone against plinking piano) and soundscape (the warm din of restaurants and the dry rhythms of hospitals) provides lucid backing for the actors. The directors thoughtfully block the transitions using their cast as stage hands (which Paul Melone tried to do in last year’s Fat Pig on the same stage, and didn’t quite succeed), making the in-between scenes a dream-like extension of the show. These same actor/stagehands (smartly trussed up like homeless people by costume designer Rachel Padula Shufelt) also manipulate some of the supernatural forbearing of the Angel, unseen by the characters on stage. In Prior and Harper’s joint hallucination, it is a raggedly dressed man who places a white feather in Prior’s lap, instead of it falling from the heavens. In a hospital during one of Prior’s checkups, a similarly clad Susan Nitter storms up the aisle, opens a large book above her head, which accompanied by flourish of light and a heavenly chorus substitutes for the book bursting through the floorboards, flaming (as the script indicates). These moments epitomize the production’s key strength; here the directors not only found a method to bring Kushner’s ideas to life within their means, but added to absurdity of the action with the modesty of the effect. The show is rarely overwhelmed by the script’s technical demands, and instead gives the actors’ capable, and often captivating, characterizations the floor.

cast all do double-, and triple- duty (including Nitter, left, who can now add Drag King to her resume) to populate the Roberts Studio with all of the aforementioned principle players, as well as some assorted nuts and phantoms. The story also location-hops without abandon, taking place in the parks and apartments of the city, as well as the dreamscapes and tundras of its character’s imaginations. Directors Southerland and Curran Willis, aided by the unfussy work of their capable design team, manage to keep Millennium moving at an admirable pace. Laura McPherson’s industrial wasteland of a set facilitates all of the necessary simultaneous staging (which often bothers me, but didn’t here), but seemed a little flimsy for the physicality of the production. More impressive were sound designer Nathan Leigh and lighting designer John Melinowki’s nuanced contributions. Melinowski clearly delineates all of the different locations of the play, and baths all of the more fantastic scenes in a hallucinogenic black light glow, and both Leigh’s musical compositions (dark sliding saxophone against plinking piano) and soundscape (the warm din of restaurants and the dry rhythms of hospitals) provides lucid backing for the actors. The directors thoughtfully block the transitions using their cast as stage hands (which Paul Melone tried to do in last year’s Fat Pig on the same stage, and didn’t quite succeed), making the in-between scenes a dream-like extension of the show. These same actor/stagehands (smartly trussed up like homeless people by costume designer Rachel Padula Shufelt) also manipulate some of the supernatural forbearing of the Angel, unseen by the characters on stage. In Prior and Harper’s joint hallucination, it is a raggedly dressed man who places a white feather in Prior’s lap, instead of it falling from the heavens. In a hospital during one of Prior’s checkups, a similarly clad Susan Nitter storms up the aisle, opens a large book above her head, which accompanied by flourish of light and a heavenly chorus substitutes for the book bursting through the floorboards, flaming (as the script indicates). These moments epitomize the production’s key strength; here the directors not only found a method to bring Kushner’s ideas to life within their means, but added to absurdity of the action with the modesty of the effect. The show is rarely overwhelmed by the script’s technical demands, and instead gives the actors’ capable, and often captivating, characterizations the floor.

harshness and vulnerability allows him to nail some of the play’s funniest and most somber moments. Maurice Parent, as Prior’s fiercely protective compatriot, is able to match Reilly’s charisma, and makes his own character’s barbs fly. Less apparent, but equally distinguished, is the subtler work of Bree Elrod and Susan Nitter as Harper and Hannah Pitt. Elrod’s unabashed instability conjures a jaded sadness that gave the character a refreshingly light presence. Nitter, in contrast to Elrod’s child-like Harper, lends Hannah Pitt a grounded world-weariness. Her crumbling response to the late-night coming out of her son was one of the more vivid moments that, in my mind, blew its miniseries counterpart out of the water (no small task considering it employed no less than Meryl Streep). And perhaps even more impressively she endows a secondary role of hers, the quietly grudge-holding ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, with an electric intensity.

harshness and vulnerability allows him to nail some of the play’s funniest and most somber moments. Maurice Parent, as Prior’s fiercely protective compatriot, is able to match Reilly’s charisma, and makes his own character’s barbs fly. Less apparent, but equally distinguished, is the subtler work of Bree Elrod and Susan Nitter as Harper and Hannah Pitt. Elrod’s unabashed instability conjures a jaded sadness that gave the character a refreshingly light presence. Nitter, in contrast to Elrod’s child-like Harper, lends Hannah Pitt a grounded world-weariness. Her crumbling response to the late-night coming out of her son was one of the more vivid moments that, in my mind, blew its miniseries counterpart out of the water (no small task considering it employed no less than Meryl Streep). And perhaps even more impressively she endows a secondary role of hers, the quietly grudge-holding ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, with an electric intensity.

Christopher Webb as Louis certainly did his role justice, giving Louis’s political tirades the  dexterity and arrogance they need. Unfortunately, he takes the easy road in the latter half of Millennium, emphasizing Louis’s horniness in lieu of his emotional desperation, making the already selfish character even less likeable. Sean Hopkins is unobtrusive as Joe (which may very well be written into the role) but one does wish for a few more heart-grabbing moments to texture the low-key interpretation. Richard McElvain, however effective, seemed all too quick to indicate his character’s failing health in a sub par vocal delivery, often swallowing Cohn’s muscular phrases, which de-clawed the political titan too early to show any visible descent.

dexterity and arrogance they need. Unfortunately, he takes the easy road in the latter half of Millennium, emphasizing Louis’s horniness in lieu of his emotional desperation, making the already selfish character even less likeable. Sean Hopkins is unobtrusive as Joe (which may very well be written into the role) but one does wish for a few more heart-grabbing moments to texture the low-key interpretation. Richard McElvain, however effective, seemed all too quick to indicate his character’s failing health in a sub par vocal delivery, often swallowing Cohn’s muscular phrases, which de-clawed the political titan too early to show any visible descent.

Lastly, there is Elizabeth Aspenlieder who, other than in brief appearances as Prior’s nurse and an engagingly neurotic homeless woman, is only heard in voiceover and seen fleetingly in the conclusion as the Angel. This conclusion is, both understandably and troublingly so, the weakest moment of an impressive show. Kushner’s demand for an angel to burst through an apartment ceiling would be a little much for any theatre company, let alone to the little-engine-that-could BTW has shown themselves to be thus far. So it makes perfect sense that it would be this high-flying moment that they fail to bring convincingly down to earth; besides whirling colored lights and some sliding panels, the entrance of the Angel offers little earth-shattering spectacle. This is completely expected, although the quick glimpse we get of the Continental Principality herself was enough to makes me hesitant of the Angel-heavy Perestroika. In Shufelt’s least savory costuming choices, Aspenlieder looks ready for a senior prom, and even her delivery of her one line seemed a little humble. I wonder how the company will fare with Perestorika, which is rich with these absurd flights of fancy, the least of which is a wrestling match with the angel. But all worries aside, this misstep did, it anything, allow me to reflect on how few there were before it.

ceiling would be a little much for any theatre company, let alone to the little-engine-that-could BTW has shown themselves to be thus far. So it makes perfect sense that it would be this high-flying moment that they fail to bring convincingly down to earth; besides whirling colored lights and some sliding panels, the entrance of the Angel offers little earth-shattering spectacle. This is completely expected, although the quick glimpse we get of the Continental Principality herself was enough to makes me hesitant of the Angel-heavy Perestroika. In Shufelt’s least savory costuming choices, Aspenlieder looks ready for a senior prom, and even her delivery of her one line seemed a little humble. I wonder how the company will fare with Perestorika, which is rich with these absurd flights of fancy, the least of which is a wrestling match with the angel. But all worries aside, this misstep did, it anything, allow me to reflect on how few there were before it.

I will be the first to say that this is a production that feels good to praise, which could undoubtedly have influenced my enjoyment of it. Boston Theatre Works is a company making a visible effort to expand, and Angels is an admirable effort in doing so both in terms of the financial and artistic risk it requires. Could the presentation be slicker? Undoubtedly so. Would it have made the overall experience much better? Questionable. Although a sleeker showing may have given Kushner’s prose the room to breath (without worrying about how a bench was going to make its way offstage), the rough-around-the-edges feeling of BTW’s Millennium works, as it just made clearer the flesh and blood lives its character lead; some of the transitions may have been clunkier than intended, but it seems almost fitting. Why should a play that has struggle in its blood be effortless (a word that I am sure will never be used to describe this Angels; on the contrary, from the scene changes to the scenes themselves, this production is fueled by an unrelenting effort)